Geothermal energy

The first signals of how humans used geothermal energy, dates of thousands of years ago. Evidence shows that some cultures took advantage of this power for cooking and heating. All over the world it is possible to observe geysers and bath in thermal waters, which are in fact a representation of this natural force.

Geothermal energy is simply the heath of the Earth, power that comes from the inner part of our planet contained in the rock and fluids beneath the crust. It is a clean and sustainable source of energy, which can generate electricity and heat or cool buildings directly.

Moreover, geothermal energy is effective, reliable and environmentally friendly but limited to tectonic plate boundaries. In this regard, recent technological advances considerably expanded the useful territory, and the range and size of the resources. In theory, the Earth’s geothermal resources might be more than adequate to supply humanity’s energy needs but only a very small fraction may be profitably exploited.

The first geothermal plant that generated energy was established in Larderello, Italy, in 1904. Nowadays more than 20 countries generate geothermal energy, being the USA the world largest producer. However, international cooperation bodies are supporting the development of this industry in strategic regions with high Earth power potential.

How does it work?

Geothermal energy works with underground reservoirs of steam and very hot water, which drives turbines linked to electricity generators. There are different methods to extract this power from the subsoil, (1) dry steam takes steam out of fractures in the ground and uses it to directly drive a turbine; (2) flash plants pull deep, high-pressure hot water into cooler, low-pressure water and the steam generated is used to drive the turbine; (3) in binary plants, the hot water is passed by a secondary fluid with a much lower boiling point than water, this causes the secondary fluid to turn to vapour, which then drives a turbine; (4) EGS or enhanced geothermal system does not need of water to generate energy but uses the hydraulic simulation to create power resources from hot dry rock, then cool water is injected back into the ground to heat up in a closed loop. This technique, adapted from previous experiences from oil and gas extraction, does not use toxic chemical, so the possibility of environmental damage is low.

Environmental effects and renewability

The geothermal energy is considered a renewable energy; the heat extraction rate from the Earth’s heat content is minimal but extraction must be carefully monitored to avoid local depletion. Even in localities, where the resources were over exploited, the soil has the potential to replenish and recover its full potential, if production is reduced.

Although geothermal energy can be produced without the use of any fossil fuel such as oil, gas or coal, it might bring some environmental issues that have to be considered. Especially hydrogen sulphide (H2S), carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) represent an environmental concern when released as well as the disposal of some polluted fluids. In this regard, EGS technique uses these fluids and injected them back to the Earth to both stimulate production and reduce environmental risk. In general terms, geothermal systems require a tiny quantity of freshwater and land if compared with traditional and other renewable energy systems.

Geothermal energy supply for the long term

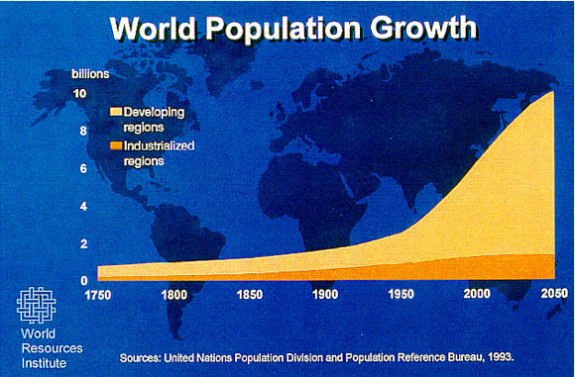

The global energy supply system is threatened by an excessive demand of electricity for the next 20 years. Old and contaminant coal plants and public resistance to expand nuclear power are, among many others, limitations that incentives to invest in the development of more efficient energy resources as well as in infrastructure changes needed to include renewables at large.

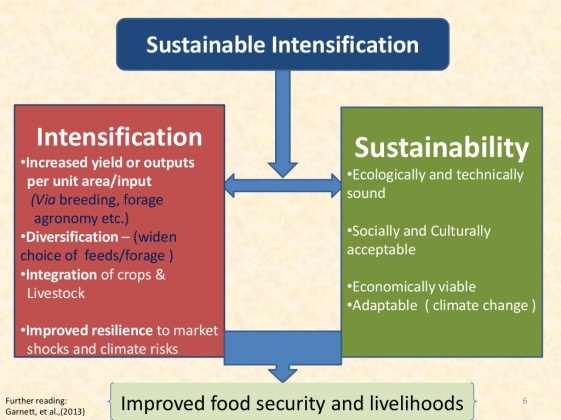

As aforementioned, international bodies are turning to invest in the research and development of geothermal energy; cooperation programs now take place in different regions in the world. Expansion of geothermal energy for electricity generation can lead to a fundamental shift in regional production systems, which need to be accompanied by regional development strategies to minimize economic, social and environmental risks; it also requires the development of complementary technologies as well as human capital.

There are four key elements of assessment:

- Resource – quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the current state of knowledge regarding geothermal resources

- Technology – analyses of subsoil and surface system components and field testing experiences

- Environmental constraints – establish an update policy overview for sustainable development, climate protection and energy security.

- Social–economic attributes – set strategies to promote the empowerment of stakeholders including capacity building, facilitation of knowledge transference and local ownership.

All previous key elements have to be aligned to explore feasibility of a new or improved technology. For this purpose, cooperation programs may include basic and applied research aiming to foster a resource-efficient and market-affordable energy technology.

So far, geothermal energy has prove to be:

- Large, local, indigenous, accessible base load power resource

- Fits portfolio of sustainable renewable energies options

- Scalable and environmentally friendly due to small foot prints and low emissions

- Technically feasible, the technology to capture and extract EGS are being tested

- Positive economic projections

- Reasonable research cots in comparison with other alternative energy programs

A study supported by the MIT states that geothermal can provide a large amount of sustainable, indigenous, clean, base load and affordable energy.

For this to happen, local ownership has to be addressed in order to assure a successful execution of the programs by supporting local development efforts, and creating social acceptance around the development of the geothermal industry.

B Corps are companies that, voluntarily, meet rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, transparency and accountability; aspects that will lead them to create benefit not only for shareholders, but also for all stakeholders (community, workers and environment). The main purpose is that business should aspire to do no harm and benefit all (including the decrease of poverty, rebuild of communities, preservation of environment and create proper places to work).

B Corps are companies that, voluntarily, meet rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, transparency and accountability; aspects that will lead them to create benefit not only for shareholders, but also for all stakeholders (community, workers and environment). The main purpose is that business should aspire to do no harm and benefit all (including the decrease of poverty, rebuild of communities, preservation of environment and create proper places to work).